The romantic notion of Africa invokes visions of

lions stalking prey amongst dried elephant grass and towering giraffes foraging

from baobab trees. The reality however, is

that large mammals have been poached to endangerment largely during colonialism,

and are now confined primarily to national parks and game reserves. In our area, the only land predators

remaining are spotted hyenas. They come

down from the mountains at night and roam the village as people sleep, often eliciting

a telltale chorus of howls from the dogs.

These nocturnal visitors leave little trace besides the occasional

slayed livestock. Last month, one of our

nearest neighbors awoke with the sunrise to find a hyena had slaughtered one of

his goats. This happened within 20 m of

our bedroom, but we did not even stir.

Hyenas are feared because they are associated with dark magic and death

in Chewa folklore, but they represent little threat to humans. The exception being drunks, who after downing

too much local cornmeal beer, find themselves at the Lilongwe nature sanctuary

after dark. A few drunks who slept off

their stupor in this tranquil area of the nation’s capital have been picked off

by hyenas in recent years.

I’ve wanted a glimpse of the elusive spotted hyenas,

and have heard that they are plentiful in the woods surrounding the firing

range where the soldiers from the nearby military base train. The firing range is halfway down the 6 km

dirt road stretching from the village to the paved M14 road to Salima. Besides one small village, the entirety of

the road is surrounded by miombo woodland, making it terrific habitat for

wildlife. A few times, our co-worker has

asked us to drive and pick her up at the turn-off by the main road at night,

since the bicycle taxis that are the main mode of transport down this stretch

don’t operate past sunset. Chris and I

have turned these opportunities into what we call the “poor man’s game drive.” Chris drives slowly down the dark road in

first gear, and I point a bright flashlight out the window, scanning the trees

for animals, specifically hyenas. We’ve

seen half a dozen civet cats, and a bouncing pair of glowing eyes from a tree that

must have been a bush baby (the world’s most adorable nocturnal primate), but

no hyenas.

Over Christmas, we decided to upgrade from the poor

man’s game drive and traveled to Liwonde National Park in southern Malawi with

two co-workers. While living in Zambia

we had the good fortune of being able to visit three national parks, but this

was our first safari with our own vehicle.

|

| A fish eagle, Malawi's national bird |

The next day, we awoke early to arrive at the park

gates as they opened at 6am.

Unfortunately, we learned that the rains had washed away a bridge

within, making much of the 50 km long park inaccessible. The woman soldier at the gate, correctly

appraising Chris as someone who liked to push the limits, warned him

The next day, we awoke early to arrive at the park

gates as they opened at 6am.

Unfortunately, we learned that the rains had washed away a bridge

within, making much of the 50 km long park inaccessible. The woman soldier at the gate, correctly

appraising Chris as someone who liked to push the limits, warned him repeatedly to turn around before the bridge to avoid getting stuck in the mud, since no one would come to our rescue. That left us with an area with a 10 km radius to explore. The backdrop of the park itself is gorgeous, with tall palm trees lining the river, expansive flood plains of burnt grasses fading into miombo forest, all bordered by blue mountains. We saw all kinds of antelope: large greater kudus with oversized ears, delicate tan impala with huge hooked antlers, and shaggy waterbucks. We crept the car slowly towards them for pictures, but sudden movements made them flee. We also saw warthogs, ancient-looking creatures which are built so awkwardly that they have to kneel with their front legs to graze. At one point we passed a family, which startled and ran away with their bristly tails held straight in the air.

After driving around for a couple of hours, we

returned to the lodge to cook breakfast: pancakes cooked over the fire and

drizzled with precious Vermont maple syrup.

We returned for another game drive in the late afternoon. This time, Chris wanted to drive closer to the

river on the smaller trails, like he’d seen a guide in a safari 4x4 do earlier

that day. This area was covered in deep

mud, unlike the main road. Much of the

ride was spent careening around in the mud and sliding, narrowly avoiding

trees. It was a lot of fun, but I’d have

enjoyed it more if it wasn’t in the company vehicle that I was responsible for. The highlight of this drive was turning a

corner and seeing a solitary, younger elephant standing by the road, playing in

a large mud puddle.

| |||||||||||||

| Hornbill (think Zazu from The Lion King) |

|

| A herd of greater kudu and a baboon |

Another excursion this month was to Cape Maclear,

which is situated almost on the far southern end of the 365 km long Lake

Malawi. One of the only accessible parts

of the lake to face northwest, it offers protection from the winds and

spectacular sunsets. Cape Maclear is a

quintessential Malawian fishing village melded with lodges catering to European

backpackers, and it has a laid-back, spirited atmosphere. Like many notable areas in this region, it

was visited and named by the Scottish explorer and missionary David

Livingstone, who named it after the Astronomer Royal at the Cape of Good Hope,

Thomas Maclear. Livingstone had

Another excursion this month was to Cape Maclear,

which is situated almost on the far southern end of the 365 km long Lake

Malawi. One of the only accessible parts

of the lake to face northwest, it offers protection from the winds and

spectacular sunsets. Cape Maclear is a

quintessential Malawian fishing village melded with lodges catering to European

backpackers, and it has a laid-back, spirited atmosphere. Like many notable areas in this region, it

was visited and named by the Scottish explorer and missionary David

Livingstone, who named it after the Astronomer Royal at the Cape of Good Hope,

Thomas Maclear. Livingstone had  such an

appreciation for its beauty that it was chosen as the original site of his

mission.

such an

appreciation for its beauty that it was chosen as the original site of his

mission.

Our organization has a partnership with a tour

operator that had just opened a new lodge on the western end of Cape, so we

were invited to a weekend of complimentary meals, lodging and water sports to

celebrate its launch. In addition to

mingling with other expatriates working in Malawi and enjoying a new side of

the lake, we also were able to go snorkeling and banana boating. We went out in the speedboat to a small,

rocky island and snorkeled among the vibrant, neon-colored cichlids that Lake

Malawi is known for. It was like floating

in a giant tropical fish tank. Later

that day, we piled on an inflatable, banana-shaped raft pulled by the

speedboat. It was pretty unstable and we

bounced high in the waves left in the boat’s wake, so we fell off often. But riding on it at high speeds with the wind

on our faces and spray from the lake kicking up, half expecting that every

turbulent patch would cause us to tumble into the water, was exhilarating.

Malawi is only the size of the state of Pennsylvania, and nearly one quarter of the country is freshwater lake, but there is tremendous geographical diversity. An hour south of Liwonde National Park lies the breathtaking Zomba Plateau. Zomba was Malawi’s colonial capital, and was claimed to be the most stunning, picturesque capital anywhere in the British Empire. Rising to an elevation of 6,836 feet, the plate

High on the plateau, options for accommodation are

limited. The Sunbird Kuchawe’s prices

match its opulent atmosphere, so we settled for camping at a former trout farm

that has seen better days. Our travel

companions until this part of the journey refused to camp with us, insinuating

that the farm was sketchy and looked like the set of a bad slasher movie. Their loss, since its location set amidst the

forest was really rather peaceful.

The lodges advocate hiring guides to lead tourists

around the plateau, but we had a Bradt’s guide to Malawi with a crude map of

the plateau, directions pirated off another traveler’s blog, and an optimistic

outlook on our sense of direction, so the four of us set off on a hike to find

Emperor’s and Queen’s view. Amidst the

rows of pine trees stretching off into the distance, the setting was not unlike

the Adirondacks. We enjoyed the

tranquility of being completely alone except for each other. At some point, we must have made a wrong

turn, but upon reaching the top of the road, we had a spectacular view of other

mountains in the distance.

The lodges advocate hiring guides to lead tourists

around the plateau, but we had a Bradt’s guide to Malawi with a crude map of

the plateau, directions pirated off another traveler’s blog, and an optimistic

outlook on our sense of direction, so the four of us set off on a hike to find

Emperor’s and Queen’s view. Amidst the

rows of pine trees stretching off into the distance, the setting was not unlike

the Adirondacks. We enjoyed the

tranquility of being completely alone except for each other. At some point, we must have made a wrong

turn, but upon reaching the top of the road, we had a spectacular view of other

mountains in the distance.

The next day, Chris and I were alone, and we decided

to hike to Chingwe’s hole, on the opposite side of the plateau. In a second moment of grossly overestimating our

abilities, we projected the trip to be about 3 miles one way, or one hour there

and one back. This side of the plateau

had a landscape more reminiscent of New Zealand, with green plains, moss-draped

trees, and small rivers cascading over the earthen path. This hike was also completely vertical, and

brought us up through the pine plantations, past temporary grass

shelters covered with black plastic where families lived while they harvested pine which they would later carry down the mountain to sell in Zomba town. The mountain rang with the sound of pit saws as pine was cut into planks. We did not see any trace of a larger scale logging operation; instead it seemed to be contracted to small groups of people living in villages on the plateau. We continued ascending, past the woodsmen, and finally came to a meadow. Though the view was lovely, we’d been walking for over two hours on legs sore from the previous day’s adventures. But a sign promised us that Chingwe’s hole was only one kilometer away. It must have been the longest kilometer of my life, since it took us another hour from there to reach the place. Meanwhile, dark clouds approached ominously, heralded by high winds and distant lightening flashing across the sky. We were on the highest part of the plateau in an open meadow, so being sensible and safety-minded, we doggedly continued towards Chingwe’s Hole rather than seeking shelter. Finally, we arrived at a rather inauspicious small circle of trees huddling together near the edge of a cliff.

Fog was rolling in, making it impossible to see what the circle of trees concealed. Since the storm was imminent and there was no shelter anywhere, we huddled on a wooden bench that faced what was probably a magnificent view any other time, but now was only the opaque white of endless fog. The wind blew ferociously, and we expected to be drenched with rain anytime, but it never came. With awe, we realized that we were above the storm clouds. While we were safely enveloped in a blanket of fog, beneath us, the rain pelted in sheets. All our The

rain beneath us was fierce but quick, and the fog dissipated. The view in front of us was still only white when we looked down at the map, but when we glanced back up, it was like someone had thrown open the curtain. Within a minute, the fog had vanished completely, revealing a view of the southern region’s raw beauty. Our tiredness melted away with that distant rain, and we were left with a feeling of invincibility and immortality there in the heavens.

shelters covered with black plastic where families lived while they harvested pine which they would later carry down the mountain to sell in Zomba town. The mountain rang with the sound of pit saws as pine was cut into planks. We did not see any trace of a larger scale logging operation; instead it seemed to be contracted to small groups of people living in villages on the plateau. We continued ascending, past the woodsmen, and finally came to a meadow. Though the view was lovely, we’d been walking for over two hours on legs sore from the previous day’s adventures. But a sign promised us that Chingwe’s hole was only one kilometer away. It must have been the longest kilometer of my life, since it took us another hour from there to reach the place. Meanwhile, dark clouds approached ominously, heralded by high winds and distant lightening flashing across the sky. We were on the highest part of the plateau in an open meadow, so being sensible and safety-minded, we doggedly continued towards Chingwe’s Hole rather than seeking shelter. Finally, we arrived at a rather inauspicious small circle of trees huddling together near the edge of a cliff.

Fog was rolling in, making it impossible to see what the circle of trees concealed. Since the storm was imminent and there was no shelter anywhere, we huddled on a wooden bench that faced what was probably a magnificent view any other time, but now was only the opaque white of endless fog. The wind blew ferociously, and we expected to be drenched with rain anytime, but it never came. With awe, we realized that we were above the storm clouds. While we were safely enveloped in a blanket of fog, beneath us, the rain pelted in sheets. All our The

rain beneath us was fierce but quick, and the fog dissipated. The view in front of us was still only white when we looked down at the map, but when we glanced back up, it was like someone had thrown open the curtain. Within a minute, the fog had vanished completely, revealing a view of the southern region’s raw beauty. Our tiredness melted away with that distant rain, and we were left with a feeling of invincibility and immortality there in the heavens.

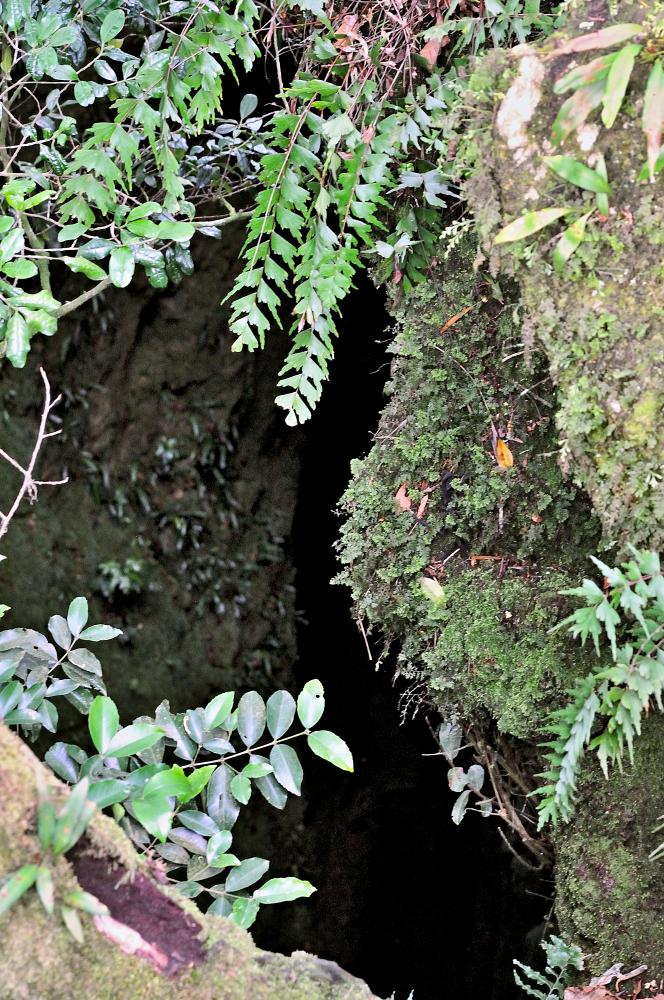

The retreating fog also left us with an unobstructed view of Chingwe’s hole, hidden in that little unassuming copse of trees. Despite the tranquil setting, Chingwe’s hole has a mysterious, deadly past. Locally, it is said to be a bottomless pit stretching into the Rift Valley. While it undoubtedly has a bottom, that abyss is littered with layers of bones. In the past, it was offered sacrifices in times of drought. They also used to throw people afflicted with leprosy into the hole, which is how it earned its name. One day they visited the hole and found the unfortunate soul tossed in the previous day to be still alive. In a weak voice that echoed throughout the 8m wide hole, he asked for a rope, chingwe in ChiChewa, to be thrown down. His request was ignored, and he eventually died of injuries or dehydration. Later, local chiefs used the hole to forever dispose of their enemies. It is rumored that former dictator Hastings Banda (1964-1994) also used the hole for this purpose. Under his reign, over 250,000 Malawians were detained without trial and tortured, and his dissenters had a tendency to die under mysterious circumstances such as car crashes, explosive blasts, or as victims of crocodiles on the Shire River.

Like the nocturnal hyenas that skulk around the village, much of our trip was shrouded in mystery. Safari is always a gamble, since there are no guarantees you’ll see animals, and it’s harder in the rainy season when the herds move further. Zomba Plateau is beautiful, but holds many secrets and no clear paths back home. We left the village without a clear plan or itinerary, intent on uncovering more about Malawi. While we did so, we’ve really only scratched the surface. This is a diverse, beautiful country, and like searching for the elusive hyenas by flashlight, I can’t wait to have more adventures in the quest for knowledge.

No comments:

Post a Comment